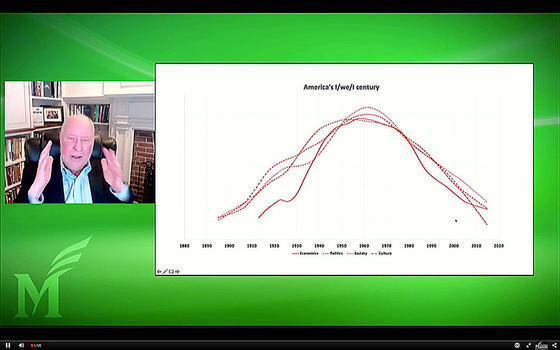

Consistently, across dozens of different measures, including social and economic equality, political division, and other indications of individualism versus collectivism, the United States experienced growing social connections that reached a peak in the 1960s, and then declined to reach record lows today. In spite of the dismal state of division we are experiencing now, there is reason for hope.

That was the message from Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett, coauthors of The Upswing: How America Came Together A Century Ago, and How We Can Do it Again, in a webinar conducted by George Mason University. The November 17 presentation was sponsored by the School of Business’ Business for a Better World Center, the Schar School of Public Policy and Government, the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution, and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

“The School of Business and Business for a Better World Center and our colleagues across campus sponsored this event to make sure that we are working together to build a better world,” said School of Business Dean Maury Peiperl.

The more than 400 students, faculty, and members of the community who registered for the event learned how America has been there before, found its way out, only to fall to a new nadir today. Deep and accelerating inequality; unprecedented political polarization; vitriolic public discourse; a fraying social fabric; public and private narcissism—Americans today seem to agree on only one thing: This is the worst of times.

During the Gilded Age of the late 1800s, Putnam described, America was similarly individualistic, starkly unequal, fiercely polarized, and deeply fragmented, just as it is today. However, as the 20th century opened, America became—slowly, unevenly, but steadily—more egalitarian, more cooperative, more generous; a society on the upswing, more focused on our responsibilities to one another and less focused on our narrower self- interest. Sometime during the 1960s, however, these trends reversed, leaving us in today’s disarray.

“Almost nobody in America thinks we’re in great shape now,” said Putnam. “We’ve reached historic levels of political polarization. Rarely, if ever, has America been as politically polarized as we are right now. The only close call, actually, is the civil war. “

Putnam examined 20 to 30 independent measures and they all tell remarkably in same story—what he calls that the “I–We–I” curve.

“At no period during the 20th century and beyond have we gotten anywhere close to full equality between Black and White Americans,” said Garrett. “However, you’ll notice that the majority of the that was made took place before the civil rights movement. We’re talking about things like life expectancy, infant mortality, high school access, high school completion, and college congratulations rates, earnings per worker, and household wealth.” During the ‘60s and ‘70s, she noted, what happened in many cases was stagnation and in some cases reversal of progress.

“One of the tragic but nonetheless simple answers is White backlash,” she said. “White Americans were [in] support of the civil rights act in principle, but when it came time to implement measures to create an equal playing field for Blacks and Whites in America, they were not so enthusiastic.”

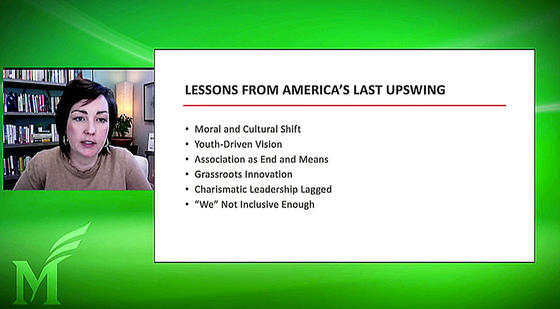

The part of the last century that is more instructive to returning to a “we” society, said Garrett, is the Gilded Age in the late 1800s and the early part of the 20th century. “It appears that Americans began to turn away from narcissism and toward egalitarianism,” she said.

“It was a time when America had shifted away from living in small towns and farms and into living in isolated, busy, commerce-oriented cities,” said Garrett. “People were lonely, much as we are today, and they realized they needed to come up with new ways of bringing people together. If we want to see another upswing today, we’re going to have to ask our fellow Americans to change from the hyperindividualistic culture of today and into something that has more of a ‘we’ ethos. We’re going to have to see a lot more activism of youth. We’re seeing that already around climate change, in the Black Lives Matter movement, and the anti-gun movement. Full inclusion can’t be something that we kick down the road again. Too often the needs of the people of color have been sacrificed on the altar of progress and we cannot make that mistake again.”

“This is not just an academic study,” said Putnam. “We try to be, as I try to be in all my work, a good social scientist, but I want to change the country. I’m not here just to describe it. We feel an obligation as citizens to try to see if we can put America on a better path to the future.”

“This book really has a strong connection to our campus,” said George Mason University President Gregory Washington. “It embodies a good bit of what we’ve encountered on our campus in terms of what we have to do going forward and in terms of where we are as a campus today. This whole idea of creating a community that values the contributions of all, that limits opportunities to none, and offers prosperity without prejudice. I believe that that’s going to be the lasting definition of the American democracy. I also believe that that is going to be the lasting definition of George Mason University.”